The Observable Universe

Heather McCalden

When I travelled to London, England earlier this year, I visited many bookstores, as I am wont to do whenever I explore an unfamiliar city. On many of the shelves, something immediately caught my eye: the minimalist white and blue covers of the British publisher Fitzcarraldo Editions. I had only heard of them from a podcast, and their reputation for publishing award-winning books, but I’ve never seen them in North American bookstores, and so I made it a mission to get a few. The Observable Universe was one of my selections.

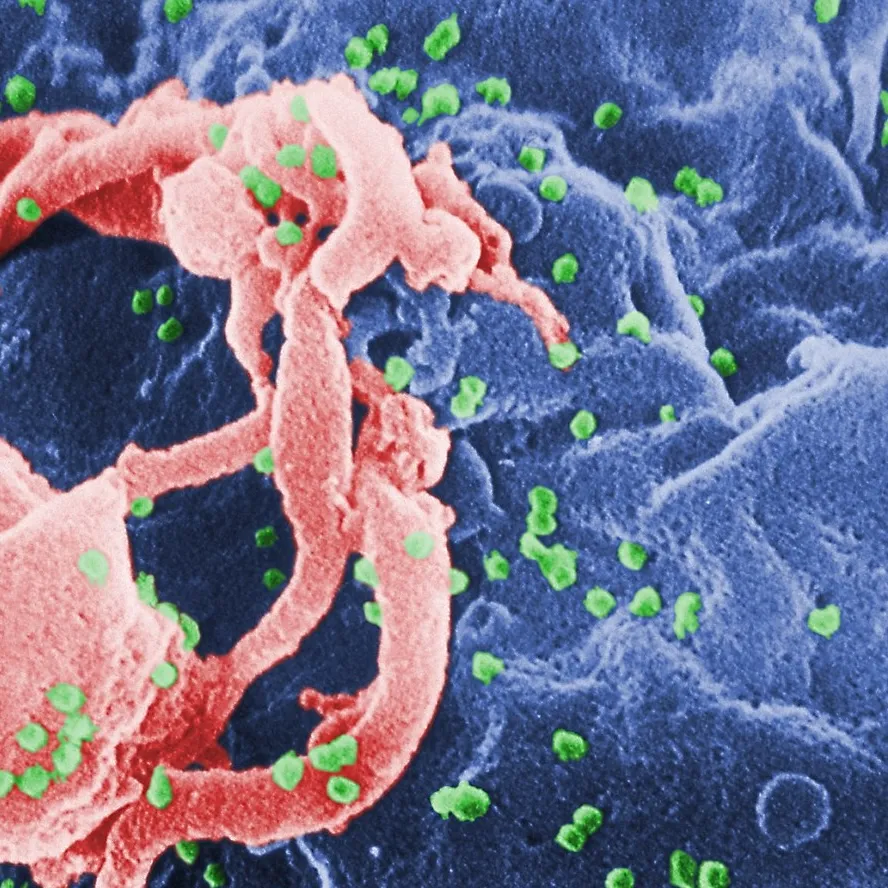

The author, Heather McCalden, lost both of her parents to AIDS when she was a child, and was raised by her grandmother. Because she was so young, she hardly knew her parents, and they’re defined more by their absence than by the scarce memories that she has of them. This memoir is her attempt to process the loss, and is made up of many “chapters,” many of which are only a few sentences long. Rarely are they more than two pages.

This unconventional structure1 leads to a somewhat fragmented reading experience. The chapters cover a range of topics: e.g. the history of scientific research on HIV and AIDS, the development of the Internet, personal anecdotes about Heather’s difficult relationship with her grandmother, noir-ish accounts of her trying to hire a private investigator to research her parents’ lives. The author’s stated intention is to form connections between all of the fragments, the most obvious one being that pieces of Internet culture go viral and spread in the same way that infectious diseases do.

I was most engaged by the more personal chapters, where she tries to understand who her parents were, culminating with hiring a professional researcher to dig up their pasts. Unfortunately, I don’t think this comes to a satisfying conclusion because there simply isn’t enough information about them, and the search comes up dry. I think there could have been a much deeper exploration of what their absence meant for her, but I felt that the book stuck to its format too rigidly: all of the little Wikipedia-like factoids about the science of infection and the history of the Internet came to overwhelm the emotional core of her story. It felt like she kept circling around what she really wanted to say, and never reached the centre.

Having said all that, it was a fascinating read, and I respect her effort to do something different.

Footnotes

-

A note on the book’s physical design: each of the chapters starts on a new page, which means that for the shorter ones, there’s a lot of blank space left over. I can’t help but think that this is a waste of paper, but that’s just me being overly pragmatic. ↩