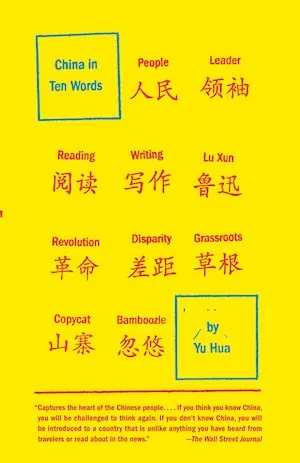

Review: China in Ten Words by Yu Hua

Compare and contrast

After my experience with Beijing Confidential, I felt compelled to expose myself to writing about China by native and contemporary authors. China in Ten Words wasn’t exactly what I was looking for—I wanted more focus on modern China, i.e. what is it like now—but it was still an enlightening read.

Each of the ten essays in this collection is a meditation on a Chinese phrase, which are all shown on the cover, in case you’re too lazy to open to the table of contents.

I was a bit impatient through the first half of the book, which deals with the author’s childhood during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960’s. It covers ground that doesn’t feel new to me because of my time with other books. I wanted him to get to the present day, which he does indeed do towards the second half. I would say that the earlier parts of the book do lay an important foundation for the rest of it, because as a whole, the book can be seen as a compare-and-contrast exercise between the time of Mao’s rule and today.

In one memorable passage, Yu describes an incident during his childhood, when he and some other kids enacted vigilante justice against a man who was illegally trading food stamps. The kids physically assaulted the man, but the man didn’t retaliate; instead, he broke down and cried in remorse.

In contrast, Yu recounts a story from more recent times, where an unlicensed street vendor stabbed and killed a government official who was trying to enforce the rules by shutting down the shop.

Yu sees this as a breakdown in the morality of the country. He seems almost nostalgic for the black-and-white authoritarianism of Mao’s day, as opposed to the everyone-for-themselves mentality of today. He acknowledges the brutality of the past, especially for the violent acts of his youth, but suggests that there was some value in unity, where everyone agrees what’s right and wrong. The man that Yu and the other kids assaulted didn’t retaliate because he knew he was breaking the rules.

So China moved from Mao Zedong’s monochrome era of politics-in-command to Deng Xiaoping’s polychrome era of economics above all. “Better a socialist weed than a capitalist seedling,” we used to say in the Cultural Revolution. Today we can’t tell the difference between what is capitalist and what is socialist—weeds and seedlings come from one and the same plant.

- Yu Hua

Personally, I’ve seen this attitude from the older generations of my family, who seem to believe that obedience is paramount. I don’t always agree, but I’ve been trying to recognize where they’re coming from. This book has further enlightened me to the differences between the two cultures that I inhabit.